ft <- c(2.5692,2.5936,2.6190,2.6320,2.6345,

2.6602,2.6708,2.6804,2.6850,2.7049,

2.7111,2.8034,2.8300,3.0639,3.1489,

3.2411,3.5701,3.9686,4.1220)

ft_avg <- mean(ft)15 The mean of a random sample

$$

$$

What we have been building up to so far is how to learn from data about the process which generated the data or about the population from which the data were drawn. However, we have not really encountered “data” yet. Our first (carefully controlled) encounter with data will be a study of what statisticians call a random sample. Imagine reaching into a population and selecting some of its members at random and measuring something about them or subjecting them to some experimental conditions and then measuring something about them. What results is a set of measurements such that each measurement i) can take more than one possible value, ii) must take a value belonging to a known set of values, and iii) takes a value which cannot be known in advance. In short, what results is a collection of random variables.

Here we will give a formal definition of a random sample and then consider the probability distribution of the mean of the values in a random sample.

15.1 Random sample

A random sample can be thought of as a set of values resulting from selecting some members of a population and taking measurements on them, possibly after subjecting them to some experimental conditions. Throughout, we will let \(n\) denote the number of values in the random sample, which we will refer to as the sample size. Formally, we define a random sample as follows:

Definition 15.1 (Random sample) A set of independent identically distributed random variables \(X_1,\dots,X_n\) is called a random sample of size \(n\).

We must admit that in the above definition we have used some terms that have not been defined yet. The first is independent. Even though we did define independence for two events \(A\) and \(B\), where we said \(A\) and \(B\) are independent if \(P(A \cap B) = P(A)P(B)\), and beyond this, we defined what it means for a collection of events to be mutually independent, we have not stated what we mean when we say that two random variables, or a set of more than two random variables, are independent. So, what is meant by the word “independence” in the above definition? Essentially, we say that two random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) are independent if the value of one does not effect the value of the other. To connect this to our definition of independence between two events, we can say that if random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) are independent, then we will have \[ P( X \in A \cap Y \in B) = P(X \in A) P(Y \in B) \] for all pairs of sets \(A\) and \(B\) which are subsets of the real numbers \(\mathbb{R}\).

The other new term appearing in Definition 15.1 is the phrase identically distributed. We say that two random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) are identically distributed if they have the same probability distribution. One way of expressing this is to say that \(X\) and \(Y\) have the same cumulative distribution function (CDF).

So, a random sample of size \(n\) is a set of random variables \(X_1,\dots,X_n\) such that i) the value of any one of them does not affect the value of any other one and ii) they all have the same probability distribution. This definition of a random sample is motivated by the oft-run experiment of drawing from a large population a certain number of members and measuring something on them; if the population is large enough, the draws can be considered independent (see the discussion on sampling with versus without replacement in Chapter 11). Moreover, since all the draws come from the same population, we can assume that all the measurements are realizations from a common distribution. Hereafter we will sometimes refer to the distribution shared by all the random variables in a random sample as the population distribution.

We may think of the random sample \(X_1,\dots,X_n\) as the values in a very simple data set. Here is an example:

Example 15.1 (Pinewood derby times) Several girls assembled and decorated pinewood derby cars and raced them, letting the cars roll down a ramp from a fixed starting point and timing (with a pretty sophisticated electronic timing system) how long it took them to cross a finish line. The finishing times are read into R in the code below.

In the pinewood derby car example, an experiment is run: tell some young girls to assemble and decorate pinewood derby cars and race them, recording the finishing times. Now, do these measurements constitute a random sample? Perhaps they do, and perhaps they do not. Let’s consider whether the finishing times are independent. I know for a fact (being the father of two participants) that there was at least one pair of sisters in the competition, who more than likely (in fact) worked simultaneously and in close proximity to each other while assembling and decorating their cars. There may have been discussion between them, or a tip they both recieved from mom or dad, which could have lead them to use similar strategies of assembly and weighting, which may in the end have caused the finishing times of their cars to be similar. Yet it may be that the dependence induced in their finishing times by all of this may be slight enough to be negligible. As for whether the finishing times represent realizations of identically distributed random variables, it seems reasonable by the following: Even though each girl may have a unique decoration style and assembly strategy, if a girl is selected at random and the finishing time of her pinewood derby car is recorded, we can regard this finishing time as a draw from some distribution; and the collection of finishing times is a collection of draws from this same distribution. So, in spite of some possibility of non-independence, we will hereafter treat the pinewood derby car finishing times as a random sample.

We may hereafter write \(X_1,\dots,X_n \overset{\text{ind}}{\sim}F\) to express that \(X_1,\dots,X_n\) are a random sample from a population with distribution \(F\). Often there are features of \(F\) that are unknown to us, and the goal of drawing the random sample \(X_1,\dots,X_n\) is to learn about these unknown features of \(F\). Here we will begin by supposing that what is of interest is the mean or expected value of the distribution \(F\). That is, if \(X_1,\dots,X_n\) is a random sample, then all of these random variables have the same expected value, say \(\mu\), which is the expected value of the distribution from which each value was drawn, that is the expected value of the population distribution. We will suppose that the value \(\mu\) is unknown to us, and that we wish to learn about the value of \(\mu\) by computing the average of the values in the random sample.

15.2 The sample mean

We first give the definition of the sample mean.

Definition 15.2 (Sample mean) Given a random sample \(X_1,\dots,X_n\), the sample mean is defined as \[ \bar X_n = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i. \]

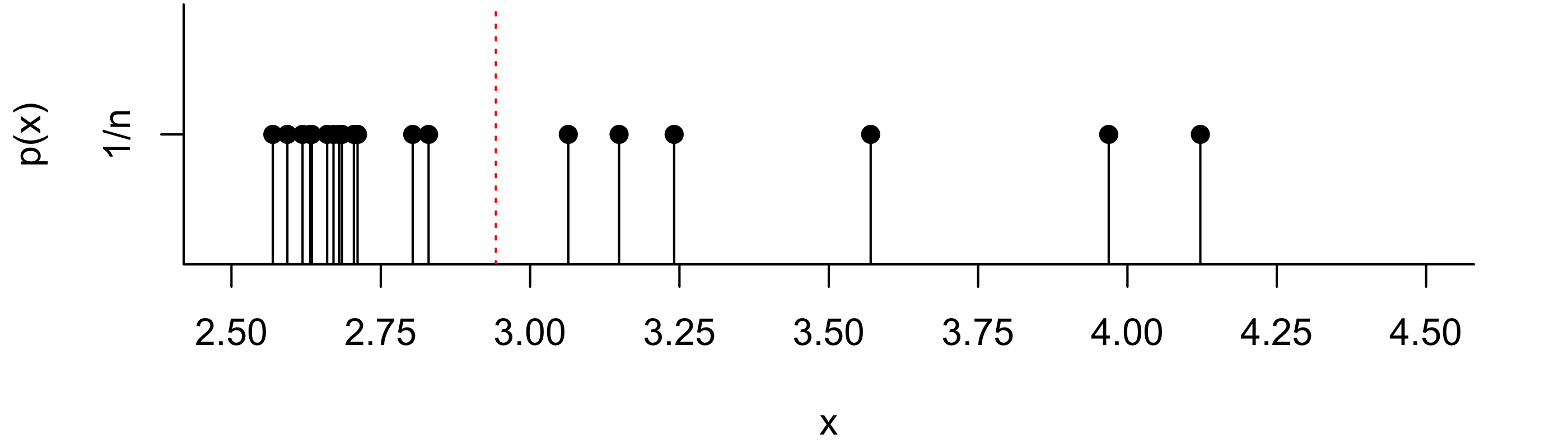

One interpretation of the sample mean is that it is the balancing point of the random sample. That is, if weights were placed on a number line at the positions of the values in the random sample, the sample mean \(\bar X_n\) gives the position at which a fulcrum would need to be placed in order to balance the number line. One can also imagine a probability mass function (PMF) which places probability \(1/n\) on each of the \(n\) data points, like the one depicted in Figure 15.1 for the pinewood derby finishing times. Then the sample mean is the expected value according to this PMF. Again, it can be viewed as the balancing point of the values.

Code

n <- length(ft)

par(mar=c(4.1,4.1,.1,2.1))

plot(ft,rep(1/n,n),type='h',yaxt='n',ylab='p(x)',xlab='x',xaxt='n',xlim=c(2.5,4.5),bty="l")

points(ft,rep(1/n,n),pch=19)

axis(2,at=1/n,labels="1/n")

axis(1,at=seq(1.5,4.5,by=0.25))

abline(v = ft_avg,col="red",lty=3)

abline(h = 0)

The sample mean \(\bar X_n\) will function as our best guess of the population mean, by which we refer to the mean of the population distribution, the distribution from which the random sample was drawn. We will denote the population mean by \(\mu\), noting that, since all of the random variables \(X_1,\dots,X_n\) have the same distribution, we have \(\mathbb{E}X_i = \mu\) for all \(i=1,\dots,n\).

So, we will use the value of \(\bar X_n\) to learn about the value of \(\mu\), which is unknown to us. In order to learn anything from the value of \(\bar X_n\), we must acknowledge that \(\bar X_n\) is itself a random variable; that is, it can take more than one possible value, and, while the range of possible values it can take is known, we cannot know in advance which value it will take. So if we were, for example, to attend another pinewood derby rally featuring cars decorated by similarly-aged girls and record the finishing times, we would observe a value of \(\bar X_n\) distinct from the value computed on the data at hand. Indeed, if we were to attend a thousand such pinewood derby car rallies, we likely never observe the same average finishing time twice; we would instead have 1000 distinct values of \(\bar X_n\). How then, one may wonder, can we possibly learn about the population mean \(\mu\) when the value of \(\bar X_n\) is different for every random sample we observe?

To answer this question, we run a thought experiment. We imagine attending, say, 1000 pinewood derby rallies and computing from each one a sample mean. Then we imagine that we make a histogram of these 1000 sample means, which would show us an estimate of the probability density function (PDF) of \(\bar X_n\). Now we ask ourselves: What will this distribution look like? Firstly, around what value is this distribution centered? Secondly, how spread out are the values in this distribution? Thirdly, we might also ask what the shape of this distribution would be.

In answer to the first and second inquiries—where the distribution of \(\bar X_n\) is centered and how spread out it is—we have the following result:

Proposition 15.1 (Mean and variance of the sample mean) Let \(X_1,\dots,X_n\) be a random sample from a distribution with mean \(\mu\) and variance \(\sigma^2\). Then we have \(\mathbb{E}\bar X_n = \mu\) and \(\operatorname{Var}\bar X_n = \sigma^2/n\).

The result tells us that the distribution of \(\bar X_n\) is centered at the population mean \(\mu\) and that its spread is governed by the variance \(\sigma^2\) of the population distribution as well as the size of the sample. We see that a larger sample size \(n\) leads to a smaller variance in \(\bar X_n\). Recalling that the variance is the expected squared distance from the mean, we can interpret the result as saying that we can expect the sample mean of a large sample to be closer to the population mean \(\mu\) than that of a small sample. In short, more data gives more accuracy.

Table 15.1 gives the mean and the variance of the sample mean \(\bar X_n\) under a few different population distributions.

| \(X_1,\dots,X_n \overset{\text{ind}}{\sim}\) | \(\mathbb{E}\bar X_n\) | \(\operatorname{Var}\bar X_n\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(\mathcal{N}(\mu,\sigma^2)\) | \(\mu\) | \(\sigma^2/n\) |

| \(\text{Bernoulli}(p)\) | \(p\) | \(p(1-p)/n\) |

| \(\text{Poisson}(\lambda)\) | \(\lambda\) | \(\lambda/n\) |

| \(\text{Exponential}(\lambda)\) | \(1/\lambda\) | \(1/(\lambda^2n)\) |

We next consider the shape of the distribution of the sample mean \(\bar X_n\).

15.3 Normal population case

In the special situation when \(X_1,\dots,X_n\) is a random sample such that the population distribution is a normal distribution, we find that the sample mean \(\bar X_n\) will also have a normal distribution. In particular, we have the result:

Proposition 15.2 (Distribution of sample mean when the population is normal) If \(X_1,\dots,X_n \overset{\text{ind}}{\sim}\mathcal{N}(\mu,\sigma^2)\) then \(\bar X_n \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu,\sigma^2/n)\).

The above result agrees with the previous result, which states that if \(X_1,\dots,X_n \overset{\text{ind}}{\sim}\mathcal{N}(\mu,\sigma^2)\) we will have \(\mathbb{E}\bar X_n = \mu\) and \(\operatorname{Var}\bar X_n = \sigma^2/n\). But it says more: This result says that if we were to collect, say, 1000 random samples and compute \(\bar X_n\) on each of these random samples, the histogram of these 1000 realizations of \(\bar X_n\) would have the bell shape characteristic of the normal distribution, centered at mean \(\mu\) and with spread governed by the variance \(\sigma^2/n\).

In the case of a normal population distribution, the above result tells us that we can find probabilities concerning \(\bar X_n \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu,\sigma^2/n)\) as follows: We may find \(P(a \leq \bar X_n \leq b)\) by

Transforming \(a\) and \(b\) from the \(X\) world to the \(Z\) world (the number-of-standard-deviations world) by \(a \mapsto (a - \mu)/(\sigma/\sqrt{n})\) and \(b \mapsto (b - \mu)/(\sigma/\sqrt{n})\).

Using the \(Z\) table (Chapter 23) to look up \(\displaystyle P\Big( \frac{a-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} \leq Z \leq \frac{b-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} \Big)\), where \(Z \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\).

And if \(q\) represents the \(p\) quantile of \(\bar X_n\), we may find \(q\) as follows:

Obtain the \(p\) quantile of \(Z\sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\) from the \(Z\) table (Chapter 23) and denote this by \(q_Z\).

Then back-transform \(q_Z\) to \(q\) with the formula \(\displaystyle q = \mu + \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} q_Z\).

Exercise 15.1 (Cell phone talk time) Let \(X\) be the number of minutes of cell-phone talk time in the last month of a randomly selected USC undergraduate. Suppose that the cell phone talk times of USC undergraduates are Normally distributed with mean \(\mu = 300\) and variance \(\sigma^2 = 50^2\).

- Find \(P(|X - 300| > 50)\).1

- Suppose you sampled \(4\) USC undergraduates and took the average of their cell phone talk times. Let the average of the four talk times be \(\bar X\). What is \(P(|\bar X - 300| > 50)\)?2

- Sample \(9\) USC undergraduates and let \(\bar X\) be the mean of their cell phone talk times. What is \(P(|\bar X - 300| > 50)\)?3

First, let’s figure out what \(|X - 300| > 50\) means: it means that \(X\) is more than \(50\) away from the mean \(300\), so we want \(P(X < 250 \text{ or }X > 350)\). For the values \(250\) and \(350\) we compute \(Z\), the number of standard deviations from the mean: \[ Z = \frac{X - \mu}{\sigma} \quad \text{ gives }\quad \frac{250 - 300}{50} = - 1 \quad \text{ and } \quad \frac{350 - 300}{50} = 1. \] We get from the \(Z\) table that \(P(Z < -1) = (Z > 1) = 0.1587\), so the answer is \(2(0.1587) = 0.3174\). ↩︎

Like before, we interpret this as \(P(\bar X < 250 \text{ or } \bar X > 350 )\). We again compute the number of standard deviations of \(250\) and \(350\) from the mean, but this time the standard deviation of our random variable is \(\sigma/\sqrt{n}\). The variance of \(\bar X\) is \(\sigma^2/n\), so our \(Z\) is going to be different: \[ Z = \frac{\bar X - \mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} \quad \text{ gives }\quad \frac{250 - 300}{50/2} = -2 \quad \text{ and } \quad \frac{350 - 300}{50/2} = 2. \] We get from the \(Z\) table that \(P(Z < -2) = P( Z > 2 ) = 0.0228\), so the answer is \(2(0.0228) = 0.0456\). ↩︎

With a sample size of \(n=9\), the standard deviation of the mean \(\bar X\) is smaller—its variability around the true mean decreases as the sample size grows. Now \[ Z = \frac{\bar X - \mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} \quad \text{ gives }\quad \frac{250 - 300}{50/3} = -3 \quad \text{ and } \quad \frac{350 - 300}{50/3} = 3. \] We get from the \(Z\) table that \(P(Z < -3) = P( Z > 3 ) = 0.0013\), so the answer is \(2(0.0013) = 0.0026\).↩︎