Code

load("data/beryllium.Rdata")

x <- beryllium$Teff

Y <- beryllium$logN_Be

plot(Y ~ x , xlab="Teff",ylab = "logBe")

$$

$$

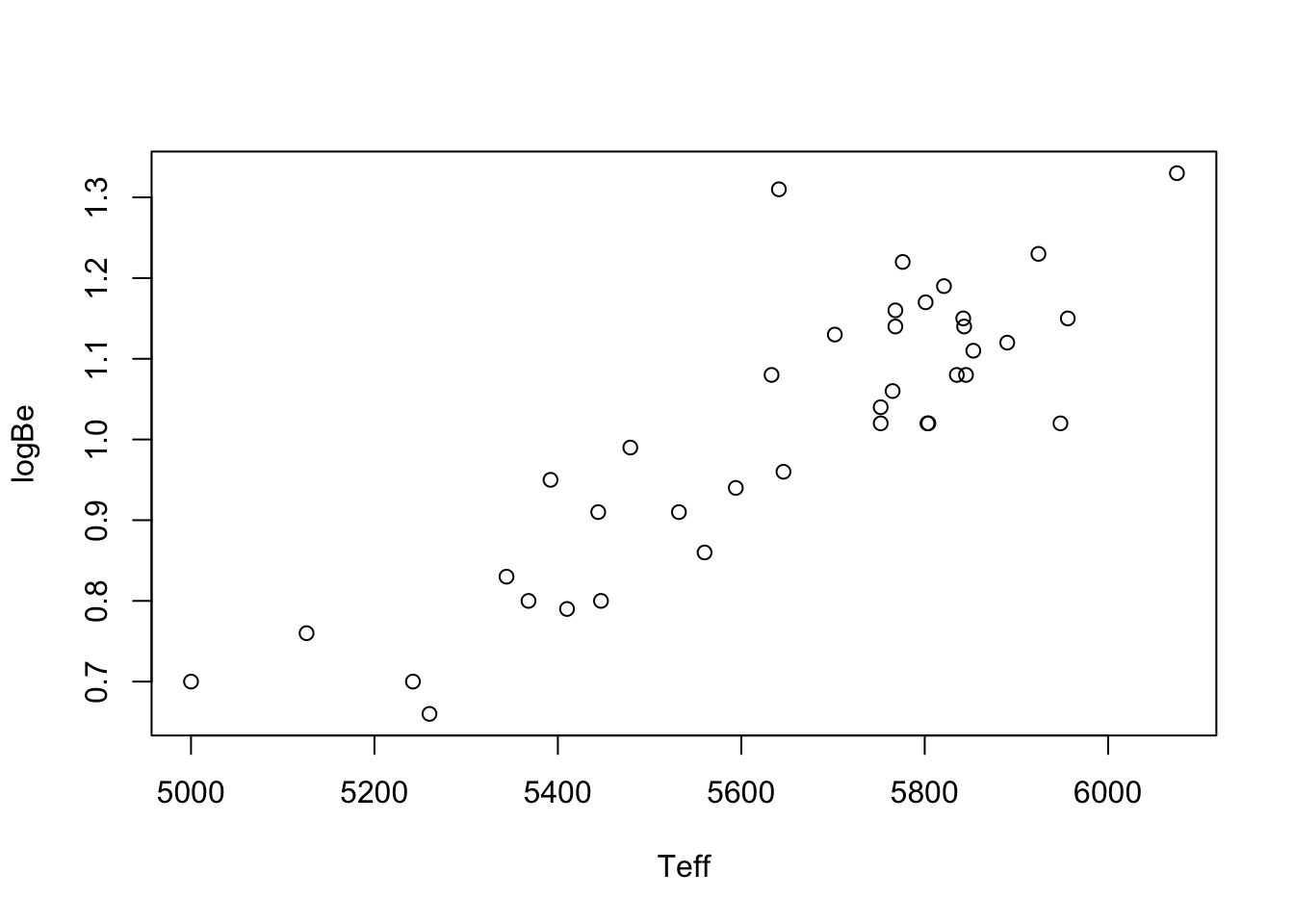

You have likely seen many plots like the one below, in which the values of one variable are plotted against the values of another. This is called a scatterplot. The data to make the plot are pairs of numbers \((x_1,Y_1),\dots,(x_n,Y_n)\). Below is an example.

Example 8.1 (Beryllium data) These data are taken from Santos et al. (2004) and can be downloaded in a .Rdata file from here. The \(x\) values in te scatterplot are temperatures of stars and the \(Y\) values are the natural log of the beryllium abundances in the corresponding stars.

load("data/beryllium.Rdata")

x <- beryllium$Teff

Y <- beryllium$logN_Be

plot(Y ~ x , xlab="Teff",ylab = "logBe")

Plots like these can be helpful for depicting the relationship between two random variables \(X\) and \(Y\). In addition, they can help researchers make predictions; for example, there is no star in the data set with temperature exactly \(5200\), but based if one were to draw a straight line through the points in the scatterplot, one could use the height of the line at \(x = 5200\) to make a reasonable guess about the log of beryllium abundance in such a star.

We first introduce what is called the correlation coefficient, which describes the strength and direction of a linear relationship between random variables, and then introduce simple linear regression analysis. The latter is a way to draw “the best” straight line through the data and to make statistical inferences—conclusions to which we can attach levels of confidence—about the linear relationship between the variables \(X\) and \(Y\).

When we suspect that two variables might be linearly related (related in such a way that one could draw a straight line through a scatterplot of their values), we often compute what is called Pearson’s correlation coefficient, which we will denote by \(r_{xY}\). This is a measure describing the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables.

Definition 8.1 (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) For data pairs \((x_1,Y_1),\dots,(x_n,Y_n)\), Pearson’s correlation coefficient is defined as \[ r_{xY} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \bar x_n)(Y_i-\bar Y_n)}{\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n(x_i - \bar x_n)^2 \sum_{i=1}^n(Y_i - \bar Y_n)^2}} . \]

It may not be clear from the formula for \(r_{xY}\) what this quantity is supposed to tell us. One fact about this value, however, which is also not immediately clear from the formula, is that \(r_{xY}\) cannot take a value outside the interval \([-1,1]\). Let’s put this fact in a big box:

Proposition 8.1 (Possible values for Pearson’s correlation coefficient) Pearson’s correlation coefficient \(r_{xY}\) must take a value in \([-1,1]\).

Back to looking at the formula: If we look for a moment at the numerator of \(r_{xY}\), we see that if \(x_i\) and \(Y_i\) tend at the same time to exceed their respective means \(\bar x_n\) and \(\bar Y_n\) and tend at the same time to fall below their respective means, the correlation coefficient should take a positive value. However, if \(x_i\) tends to be below its mean while \(Y_i\) is above its mean and above its mean when \(Y_i\) is below its mean, then \(r_{xY}\) will probably take a negative value. If \(x_i\) and \(Y_i\) tend to fall above and below their respective means without regard to one another, then \(r_{xY}\) does not know whether to be positive or negative and so takes a value close to zero.

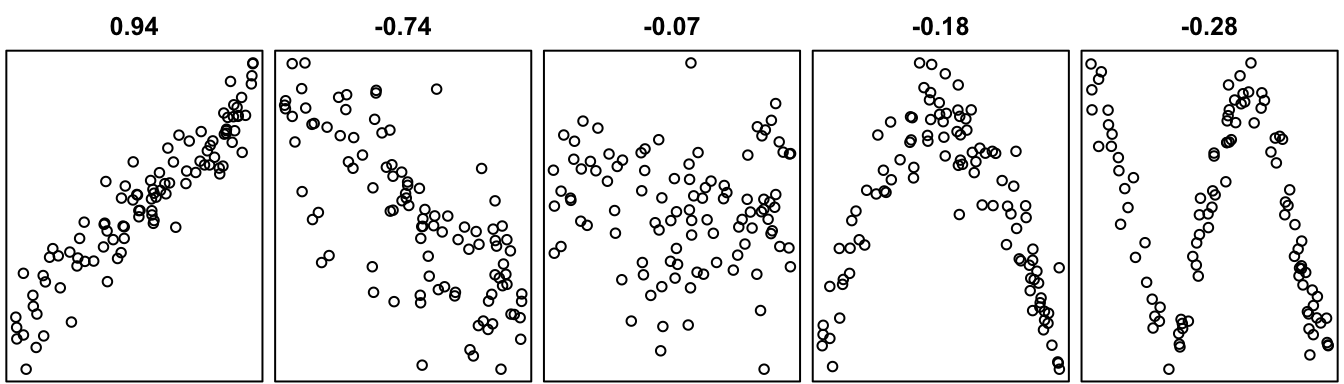

Figure 8.2 below shows a few scatterplots along with the value of Pearson’s correlation coefficient computed on the data.

n <- 100

X <- runif(n,0,10)

Y1 <- X + rnorm(n)

Y2 <- -X + rnorm(n,0,3)

Y3 <- rnorm(n)

Y4 <- -(X-5)^2 + rnorm(n,0,3)

Y5 <- cos(X/10*3*pi) + rnorm(n,0,.2)

par(mfrow = c(1,5),

mar = c(.1,.25,2,.25),

xaxt = "n",

yaxt = "n")

plot(Y1~X, main = sprintf(cor(X,Y1),fmt="%.2f"))

plot(Y2~X, main = sprintf(cor(X,Y2),fmt="%.2f"))

plot(Y3~X, main = sprintf(cor(X,Y3),fmt="%.2f"))

plot(Y4~X, main = sprintf(cor(X,Y4),fmt="%.2f"))

plot(Y5~X, main = sprintf(cor(X,Y5),fmt="%.2f"))

We may notice a few things:

As a summary, we may say that Pearson’s correlation coefficient describes the strength and direction of linear relationships. Very strong non-linear relationships, like the ones in the two rightmost panels of the plot, do not correspond to large values of Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Therefore, the quantity \(r_{xY}\) is only appropriate for describing linear relationships. If a scatterplot suggests a non-linear relationship—if you cannot draw a straight line through the data points—then it is not appropriate to use Pearson’s correlation coefficient to describe the relationship.

In statistics, the word “correlation” almost always means Pearson’s correlation, so a statistician would never say something like “what you are saying is correlated with what so and so is saying.” A statistician will not use the word “correlated” unless it is to describe the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables.

The simple linear regression model is a mathematical description of how the \(Y_i\) are related to the \(x_i\).

Definition 8.2 (Simple linear regression model) For data \((x_1,Y_1),\dots,(x_n,Y_n)\) the simple linear regression model assumes \[ Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i + \varepsilon_i \] for \(i =1,\dots,n\), where

The model states that for the value \(x_i\), the value of \(Y_i\) will be equal to the height of the line \(\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i\) plus or minus some random amount. This random amount is often called an error, but there is nothing really erroneous going on; we just don’t expect all the \(Y\) values to fall exactly on the line \(\beta_0 + \beta_1 x\), so we allow them to be different by some amount \(\varepsilon\), and we assume that values of \(\varepsilon\) will have a Normal distribution centered at zero. All of this means we expect the \(Y\) values to bounce more or less around the line, falling above and below it at random.

Having written down the linear regression model, the next task for the statistician is to use the data to estimate the unknown quantities involved. There are three: The parameters \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) giving the intercept and slope of the line, and the parameter \(\sigma^2\) giving the variance of the error terms.

We first focus on estimating \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\). Reasonable guesses at the values of \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) might be obtained by drawing, with a ruler, a line through the scatterplot which runs as much as possible through the center of the points. Although this may give reasonable results, two different people might draw two different lines, and it would hardly possible to analyze the statistical properties of such a line. We would like to have a way of drawing the line such that we can depend on its on-average being the right one, or in the sense that if we collected more and more data our method of line-drawing would eventually lead us to the true line governing the true relationship between \(Y\) and \(x\). To this end, we will introduce a criterion for judging the quality of any line drawn through the points and use calculus to find the slope and intercept values which produce the best possible line—according to the criterion.

The most commonly used criterion for judging the quality of straight lines drawn through scatterplots is called the It is equal to the sum of squared vertical distances between the data points on the scatterplot and the line drawn. If the line \(y = b_0 + b_1x\) is drawn, for some slope \(b_1\) and intercept \(b_0\), the least squares criterion is defined as the sum \[ Q(b_0,b) = \sum_{i=1}^n(Y_i - (b_0 + b_1 x_i))^2 \] of squared vertical distances of the \(Y_i\) to the height of the line \(y = b_0 + b_1x\). It is possible to use calculus methods to find the slope \(b_1\) and intercept \(b_0\) which minimize this criterion:

Proposition 8.2 (Least squares estimators in simple linear regression) The least squares criterion \(Q(b_0,b_1)\) is uniquely minimized at \[ \begin{align*} \hat \beta_0 &= \bar Y_n - \hat \beta_1 \bar x_n \\ \hat \beta_1 &= \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \bar x_n)(Y_i-\bar Y_n) }{\sum_{i=1}^n(x_i - \bar x_n)^2} = r_{xY}\frac{s_Y}{s_x}, \end{align*} \] where \(s_Y^2 = (n-1)^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^n(Y_i - \bar Y_n)^2\) and \(s_x^2 = (n-1)^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^n(x_i - \bar x_n)^2\), provided \[ \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \bar x_n)^2 > 0 \tag{8.1}\]

So, to compute the least-squares estimators of the regression coefficients \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\), one first obtains the slope as \(\hat \beta_1 = r_{xY}s_Y/s_x\) and then the intercept as \(\hat \beta_0 = \bar Y_n - \hat \beta_1 \bar x_n\).

The condition in Equation 8.1 is necessary, because we in the computation of \(\hat \beta_1\) we must divide by this sum of squares. Note, however, that \(\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \bar X_n)^2 =0\) if and only if all the \(x_i\) are equal to the same value. In this case it would be absurd to try to predict the \(Y_i\) using the values of the \(x_i\), so we do not need to fret about this condition.

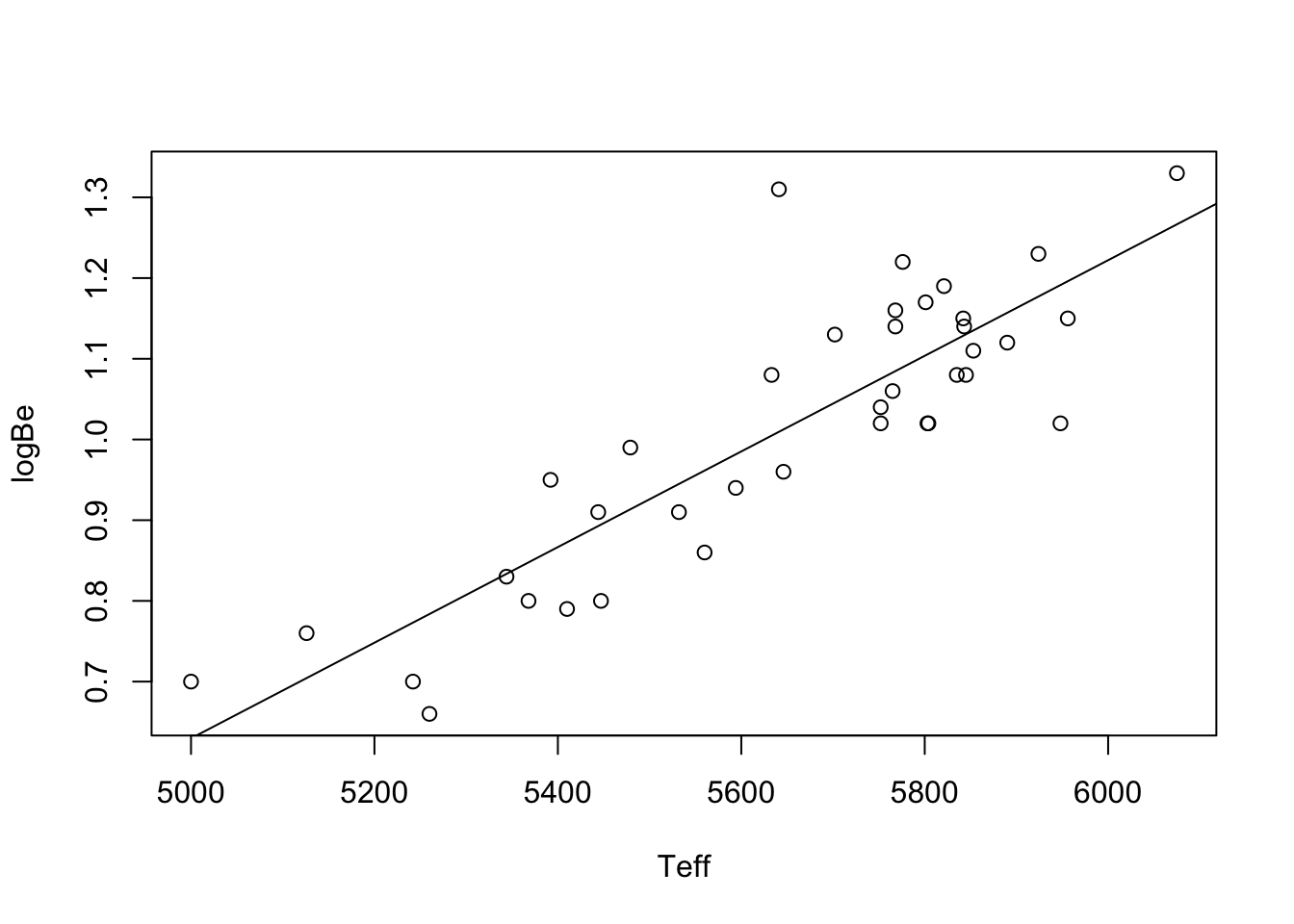

Figure 8.3 shows the scatterplot of the beryllium data with the least-squares line overlaid.

x_bar <- mean(x)

b1 <- cor(x,Y) * sd(Y) / sd(x)

b0 <- mean(Y) - b1*x_bar

plot(Y ~ x , xlab="Teff",ylab = "logBe")

abline(b0,b1)

One obtains \(\hat \beta_0 = -2.3333252\) and \(\hat \beta_1 = 5.9260046\times 10^{-4}\). One can compute these as in the preceding code, or more simply using the lm() function, as in the code below:

lm(Y~x)

Call:

lm(formula = Y ~ x)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) x

-2.3333252 0.0005926 Now that we have introduced estimators for \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\), we will consider estimating the other unknown parameter, which is the error term variance \(\sigma^2\). In order to define an estimator for this quantity, it will be convenient to define what we call fitted values and residuals. After obtaining \(\hat \beta_0\) and \(\hat \beta_1\), we define the fitted values as \[ \hat Y_i = \hat \beta_0 + \hat \beta_1 x_i \] and the residuals as \[ \hat \varepsilon_i = Y_i - \hat Y_i \] for \(i=1,\dots,n\). The fitted values are equal to the height of the least-squares line at the observed covariate values \(x_i\), and the residuals are the differences between the observed response values and the fitted values. We may think of the fitted values as predictions from our linear regression model and of the residuals reflection how far (and in what direction) our model missed the observed value.

Having defined the residuals, we now define an estimator of \(\sigma^2\) as \[ \hat \sigma^2 = \frac{1}{n-2}\sum_{i=1}^n\hat \varepsilon_i^2. \]

Y_hat <- b0 + b1 * x

e_hat <- Y - Y_hat

n <- length(Y)

sigma_hat <- sqrt(sum(e_hat^2)/(n-2))In the beryllium data example we obtain \(\hat \sigma^2 = 0.0077834\). One can use the preceding code to obtain this or one can run summary(lm(Y~x)).

summary(lm(Y~x))

Call:

lm(formula = Y ~ x)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-0.17146 -0.05198 -0.02409 0.06506 0.30047

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -2.333e+00 3.279e-01 -7.116 2.31e-08 ***

x 5.926e-04 5.799e-05 10.218 3.48e-12 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.08822 on 36 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.7436, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7365

F-statistic: 104.4 on 1 and 36 DF, p-value: 3.477e-12The quantity given as residual standard error \(\hat \sigma\).

Here is a nice result about the estimator \(\hat \sigma^2\):

Proposition 8.3 (Unbiasedness of variance estimator in simple linear regression) Under the conditions of the simple linear regression model, we have \(\mathbb{E}\hat \sigma^2 = \sigma^2\).

The above result states that the estimator \(\hat \sigma^2\) is an unbiased estimator of \(\sigma^2\). “Unbiased” means that the sampling distribution of the estimator \(\hat \sigma^2\) is centered correctly around the value it is trying to estimate; if we were to observe many realizations of the estimator \(\hat \sigma^2\), these would have an average very close to the estimation target \(\sigma^2\).

It is nice to be able to draw the best line through a scatterplot of points. We know that the least-squares line is, of any line we could possibly draw, the one that minimizes the sum of the squared vertical distances between the points and itself.

Remember the whole idea behind statistics, though? If we were to collect another data set studying the same phenomenon, we would get different data; so what can we learn from this one single data set? The line we drew through the scatterplot is really a “guess” at where the true line would be. If we could go on collecting data on all the stars in the universe, we could then draw the “true” or “population” level line. But we only have the data in our sample.

So what can we learn from it?

As we have done before with population means and variances and proportions, we will formulate some hypotheses about the true best line underneath the data and use the least-squares line to test those hypotheses. Fundamentally, we are interested in knowing whether there exists a linear relation between the \(Y_i\) and the \(x_i\). The true line is specified by the unknown values of \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\). Of these parameters, it is \(\beta_1\) which carries information about the relationship between the \(Y_i\) and the \(x_i\). We therefore concentrate on making statistical inferences about \(\beta_1\); that is, we try to learn what we can about \(\beta_1\) from the data.

What we can learn about \(\beta_1\) from the data depends on the behavior of out estimator \(\hat \beta_1\)—specifically how far away from the true \(\beta_1\) we should expect it to be. This information is contained in the sampling distribution of \(\hat \beta_1\).

Proposition 8.4 (Sampling distribution of slope estimator) Under the assumptions of the simple linear regression model we have \[ \hat \beta_1 \sim \mathcal{N}(\beta_1,\sigma^2/S_{xx}) \] as well as \((n-2)\hat \sigma^2/\sigma^2 \sim \chi_{n-2}^2\) with \(\hat \sigma^2\) and \(\hat \beta_1\) independent, so that \[ \frac{\hat \beta_1 - \beta_1}{\hat \sigma/\sqrt{S_{xx}}} \sim t_{n-2}. \tag{8.2}\]

The result in Equation 8.2 implies that under the assumptions of the simple linear regression model a \((1-\alpha)\times 100\%\) confidence interval for \(\beta_1\) may be constructed as \[ \hat \beta_1 \pm t_{n-2,\alpha/2} \hat \sigma / \sqrt{S_{xx}}. \]

alpha <- 0.05

Sxx <- sum((x - x_bar)^2)

ta2 <- qt(1 - alpha/2,n-2)

lo <- b1 - ta2 * sigma_hat / sqrt(Sxx)

up <- b1 + ta2 * sigma_hat / sqrt(Sxx)This interval with \(\alpha = 0.05\) (so a \(95\%\) confidence interval) for \(\beta_1\) in the beryllium data example is given by \((0.00047,0.00071)\). One can use the preceding code to compute the bounds of the confidence interval or one can use confint(lm(Y~x)):

confint(lm(Y~x)) 2.5 % 97.5 %

(Intercept) -2.9983088165 -1.6683415095

x 0.0004749841 0.0007102168This gives confidence intervals for both the intercept \(\beta_0\) and the slope parameter \(\beta_1\).

Beyond constructing a confidence interval for \(\beta_1\), we may also be interested in testing hypotheses about the slope parameter. We consider testing hypotheses of the form